Maybe, one of the most impressive spectacles which a polar expedition could have performed was the fire which burned the timbers of USS Rodgers and destroyed the entire ship at St Lawrence Bay (a place visited by Adolf Erik Nordeskjold in 1879), the 30th november of 1881, today almost 141 years ago.

The ship, which was at its winter quarters since the first week of october, was located almost at the same latitude than the arctic circle. It was the beginning of USS Rodger´s first and last long polar night. The days lasted at that time of the year little more than two hours so, the light of the flames, which consumed the Rodgers during three days in a row, danced and shined and illuminated the surroundings of that long polar night most certainly, provoking a deep impression in the retinas of those natives who witnessed the spectacle. A sight hard to forget, particularly when the magazine blew up the second day after the fire had started.

This wasn´t of course the only and first ship which had caught fire in the arctic regions. Whalers, sometimes fully loaded with blubber, burned down here and there when having been beset by the ice for different reasons. It is difficult to ascertain the reasons why this ships could have started burning. According to the legend of the picture below, which very likely depicts the fate of the whalers Concordia and Gay Head wrecked during the whaling disaster of 1871 where 33 ships were lost (and some were found in the last decade), their crews could have started fires "to avoid dangers to other ships", or maybe, and more likely to avoid their cargo of being stolen by other whalers. However, in the particular case of this whaling disaster, other captains, pointed at the natives as the perpetrators of the accident which could have been produced while they were collecting all possible things from the abandoned ships.

|

| American whalers crushed in the ice (1872 - 1874) Burning the Wrecks to Avoid Danger to Other Vessels |

The USS Rodgers had been sent for searching the missing USS Jeannette commanded by George De Long, which has penetrated Bering strait in 1879 in an attempt to reach the North Pole and from which nothing was heard since. At that the time, the whalers Vigilant and Mount Wollaston had also dissappeared, and the ship USRC Thomas Corwin had departed in 1880, a year before, to try to locate them. Another ship, the Alliance was participating in the searching.

During the summer of 1881, some intellegence came from the natives that the whalers had been found deserted and with some corpses still on board. Apparently, from some accounts, Mount Wollaston had sunk first and the crew came on board the Vigilant. After, both crews were finally lost after the sunk of the second vessel (this apparently comes from a piece of news from the New York Times I couldn´t find available).

After this pessimistic testimony, the Corwin joined forces with the Rodgers in the searching of the Jeannete. Jeannette wasn´t the only tragedy occurred during those years, as we are realising, but it is by far one of the most known together with Greely´s expedition which tragedy was being cooked that same year.

Few people have the crews of the lost two whalers in mind. It is very hard to think that those ships could have dragged all the men to the bottom of the sea. The testimony of the natives, that there were some corpses on the deck of one of the ships, suggests that the whaler, or maybe both of them, were still floating when they were deserted near Herald island. Surely, the crews left the ships and dragged the boats with the intetntion of reaching Wrangel island and from there, try to reach the mainland, as the crew of the Karluk did years after, but we may never known what actually happened there. Probably we have here a fascinating account of survival as mysterious as the Franklin expedition itself.

The Rodgers, which was by then a very young two years old whaler (in fact, the first american steam whaler), departed from San Francisco the 16th of june 1881 with the orders to follow the same route that the Jeannete had taken two years before.

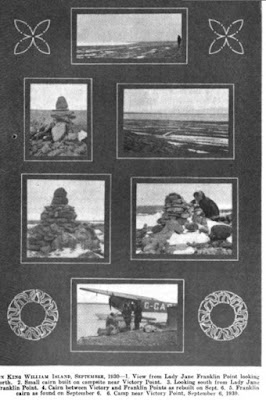

The ship had made part of its homework before being destroyed by the fire. It had explored quite succesfully the coast of Wrangel island discovering that it was actually an island, and continued exploring the waters north of it till the ice pack stopped their advance. The Rodgers sailed the same waters where Karluk was going to be destroyed by the ice years after in 1914. The ship sailed then south towards Bering Strait at the end of september and prepared to winter at the beginning of October at St Lawrence bay. There, a party of men, led by Charles F. Putnam, was sent to explore the coast to find clues from the Jeannette with provisions for a year.

|

| Route followed by the USS Rodgers while searching for USS Jeannette |

The winter had already started, and they spent two months before something awful happened. Weather hadn´t been very kind since they arrived to those shores, so the hold of the Rodgers was still heavily loaded, no wooden hut had been built yet in the shores either.

It was 8:45 a.m. of 30th november 1881 when a fire started under the Donkey boiler room, a place where an auxiliary steam boiler was placed to operate deck machinery when the main boilers were stopped. From the accounts coming from some witnesses, it is very likely that the cause of the accident was that the floor under the boiler could have autoignited because of the heat coming from the boiler and started the unstoppable fire.

Maybe a default design in this brand new model of steam ship was the underlying reason. A whole description of this dangerous and mortal event is available here, in an article published in the New York Times 21st june 1882. where the letter which Robert Mallory Berry sent with William Henry Gilder, veteran of Frederick Schwatcka expedition in search for John Franklin and correspondant from the New York Times, more than a month after the fire, saw the light.

Fires were surely the most feared dangers a ship could endure, specially when trapped by ice in the polar regions. A fire could leave unsheltered tens of men in the most horrid conditions condemning them to a certain and slow death.

Expeditions used to keep a "fire-hole" in the ice permanently opened and constant watches during the time they were in their winter quarters. The struggle to fight the fire which lasted three days, started inmediately and though it was very fierce, the crew couldn´t save the ship and almost no cargo at all, clothing included. All kind of measures were taken, they tried to suffocate it closing the hatches, threw steam over it but to no avail.

The boats, however could be saved and the defeated crew had to spend a couple of nights withouth further protection than their blankets. They tried after to retreat towards the closest siberian village of Nuniagmo, at seven miles from the landing point, without success. With all certainty, the light had been seen from the village and surely had frightened the natives who likely hadn´t seen something like before that in their entire lives. They are refered in the New York Times article as Tebanketchis? (in other places as Tehaunketchis) about which I have found no information.

Two natives, recruited at St Lawrence bay months before, were still on board the ship when the accident happened, and revealed themshelves of a very providential help to secure the safety of all onboard. They went to the village and came back with help for the castaways. The crew was splitted into several groups which were quickly distributed and lodged in the nearby villages. To some, it took eight hours to walk four miles, due to the one meter of thicknes of the snow, the bad weather and the poor condition of the men who couldn´t sleep and eat properly. Putnam, who was camped north of the bay, heard about the incident and traveled south with supplies (an important part formed by tobacco and cigarrettes) to help Rodger´s crew. It was during his return to his camp when the poor man lost his life in a very dramatic way, I talked about his sad fate some time ago here.

There, in those siberian villages, they stood till were rescued and brought to Sitka, first by the whaler North Star, and then by the other searching ship, the Corwin. Thirty one men of thirty five were landed safe and sound in june of 1882 while Berry and H. J. Hunt had departed northward the 23rd of december of 1881, following the coast in an attempt to find the Jeannette. They arrived at Nizhnekolymsk, at the banks of Kolyma river, where they heard about the awful fate suffered by some of the men from the Jeannette and helped together with the New York Herald correspondant, Jackson (No, no the same Jackson who found Nansen) in the search of the rest of the missing men. Gilder had been sent to the west to inform about the fat of the Rodgers. None of these three men were expected to come back to the east, they had to find their way westwards through Siberia, a trip which was an adeventure inside another adventure.

What happened to USS Rodgers was, there is no doubt about that, something spectacular. The natives surely talked about that phenomenon during decades. That the consequences of those improvised fireworks had been so harmless, may also be considered spectacular. It was a miracle that the only loss of the Rodgers was that of Putnam together with the deaths of the two pet dogs of the ship. The whalers which the Corwin was looking for weren´t so lucky, they were in a much more inhospitable region deprived of the presence of the natives who, feeding the Rodger´s men with rotten walrus meat and whatever edible thing they managed to find, made the impossible possible.

Bibliography:

Ice pack and tundra: an account of the search for the Jeannette and a sledge journey through Siberia