(In English below)

Os dejo aquí el link a un libro "The great Frozen land" (accesible pero en inglés) que cuenta la historia de un paseíto de 3.000 millas por la tundra siberiana que el señor Frederick George Jackson realizó montado en un trineo en 1893. Yo todavía no me lo he leído pero está en la lista de "siguientes".

Su objetivo era probar la vestimenta, el material y la comida bajo condiciones árticas invernales antes de emprender la expedición de 1894-97 para explorar el norte de la Tierra de Francisco José (80ºN), la expedición que se conocería como Jackson-Harmsworth.

Su objetivo era probar la vestimenta, el material y la comida bajo condiciones árticas invernales antes de emprender la expedición de 1894-97 para explorar el norte de la Tierra de Francisco José (80ºN), la expedición que se conocería como Jackson-Harmsworth.

|

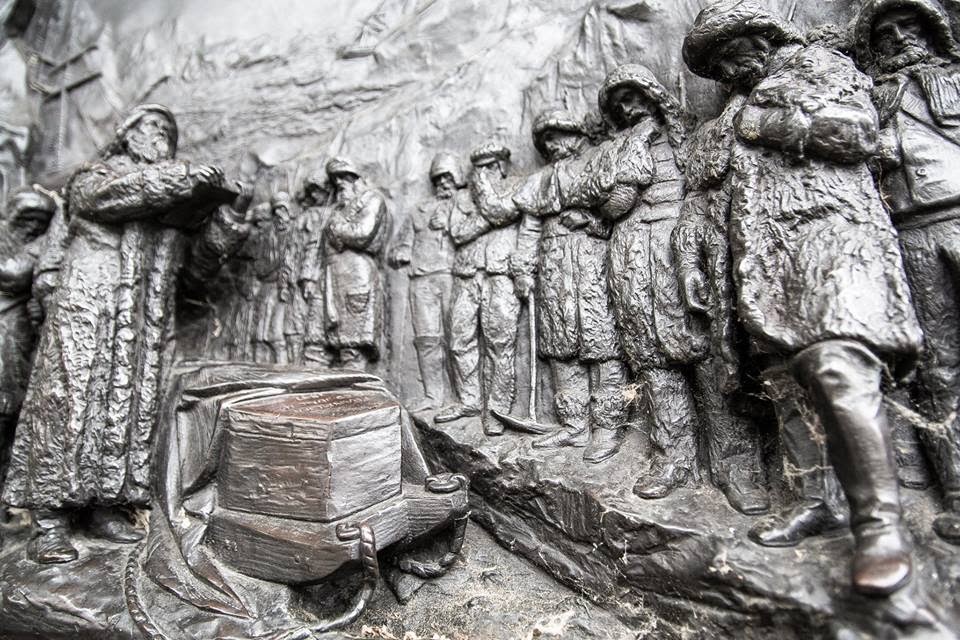

| Frederick George Jackson |

Eligieron la Tundra siberiana porque como él mismo dice en el prefacio del libro:

"Como mucha gente sabe, las tundras bajas del ártico ruso y Siberia, aunque son fácilmente accesibles por el este, oeste y sur de los confines de la civilización, poseen un clima invernal de una severidad tan grande que no solo supera el rigor de muchas regiones que se encuentran mucho mas al norte, sino que realmente presentan menores temperaturas que las registradas en la cuenca ártica. Por lo que es en las heladas Tundras de Siberia donde encontraremos lo que ha sido denominado EL POLO DEL FRÍO EXTREMO".

Para mi personalmente, Jackson es un personaje un tanto desconocido y puede que lo sea para muchos de vosotros también. Casi todos los forofos de lo polar nos hemos siempre centrado en los grandes exploradores que o bien llegaron o bien intentaron realizar grandes hazañas como llegar andando, en barco, en globo o en avión al Polo Norte, Polo Sur, cruzar el paso del Noroeste, etc. Pero dejamos a un lado muchas veces a aquellos que realizaron expediciones de exploración que podríamos considerar "de detalle" por llamarlo de alguna forma. Aquellas expediciones se centraban solo en una pequeña parte de la geografía ártica, que normalmente había sido descubierta por otros y la cartografiaban con esmero, midiendo y registrando todo tipo de datos científicos y meteorológicos.

En mi caso, conozco a Jackson sobre todo porque fue él durante esa segunda expedición a la Tierra de Francisco José quien se tropezó por pura casualidad con Nansen que volvía de su expedición al Polo Norte. La historia de Nansen pudo haber sido muy distinta si este encuentro no se hubiese producido, esta afirmación es objeto de conjetura todavía hoy en día. Es posible que Jackson salvase la vida de Nansen, y es posible también que si no hubiese sido por este encuentro, Jackson sería uno de esos exploradores de "segunda" de los que apenas habríamos oído hablar.

En mi caso, conozco a Jackson sobre todo porque fue él durante esa segunda expedición a la Tierra de Francisco José quien se tropezó por pura casualidad con Nansen que volvía de su expedición al Polo Norte. La historia de Nansen pudo haber sido muy distinta si este encuentro no se hubiese producido, esta afirmación es objeto de conjetura todavía hoy en día. Es posible que Jackson salvase la vida de Nansen, y es posible también que si no hubiese sido por este encuentro, Jackson sería uno de esos exploradores de "segunda" de los que apenas habríamos oído hablar.

|

| Jackson - Nansen encounter Junio 1896 |

Con o sin encuentro, Jackson demostró ser merecedor de la fama que ahora parcialmente tiene. Completó el reconocimiento del archipiélago descubierto (al menos fueron los primeros que se lo adjudicaron) por los austriacos Karl Weyprecht y Julius Von Payer en 1873. Engañado por los exploraciones superficiales de la expedición precedente, Jackson demostró que la Tierra de Francisco José no era una extensión de tierra que llegaba hasta el polo, como se creía, sino un archipiélago que no superaba en su punto más septentrional los 81 ºN. Algo parecido a lo que le ocurrió a la expedición Danesa de Jorgen Bronlund, que por fiarse de los mapas dibujados por Peary acabaría pereciendo en el norte de Groenlandia en 1908 junto con dos de sus colegas.

Ahora que estoy leyendo sobre Cook me doy cuenta de lo potencialmente peligroso que era dar crédito a ningún mapa, por fiable que la fuente pudiera parecer. Los mapas posteriores al tratado de Tordesillas movían tierras e islas a placer para situarlas en ubicaciones donde fueran más conveniente para según que potencia. Ficticias bahías como la de Poctes Bay en King William Island podría haber conducido a la expedición de Franklin a una muerte lenta por inanición y escorbuto en 1846, pero lo más sorprendente es que aún en épocas relativamente recientes en el siglo XX, un mapa equivocado podía todavía matar exploradores bien preparados y entrenados como ocurrió en el caso de la expedición danesa. Yo, gracias a Dios, no me separo nunca de mi GPS, y espero que nunca me deje colgado cuando realmente lo necesite.

Ahora que estoy leyendo sobre Cook me doy cuenta de lo potencialmente peligroso que era dar crédito a ningún mapa, por fiable que la fuente pudiera parecer. Los mapas posteriores al tratado de Tordesillas movían tierras e islas a placer para situarlas en ubicaciones donde fueran más conveniente para según que potencia. Ficticias bahías como la de Poctes Bay en King William Island podría haber conducido a la expedición de Franklin a una muerte lenta por inanición y escorbuto en 1846, pero lo más sorprendente es que aún en épocas relativamente recientes en el siglo XX, un mapa equivocado podía todavía matar exploradores bien preparados y entrenados como ocurrió en el caso de la expedición danesa. Yo, gracias a Dios, no me separo nunca de mi GPS, y espero que nunca me deje colgado cuando realmente lo necesite.

Here I add the link to a book called "The great Frozen land" which tells the story of a short walk of 3.000 miles by the siberian Tundra which Mr Frederick George Jackson did riding a sledge in 1893. I haven´t read it yet but it is in my list of "Nexts".

His target was to test the clothing, equipment and food under arctic winter conditions before beginning his expedition of 1894-97 to explore the north of Franz Joseph Land (80ºN), the expedition which would be called Jackson-Harmsworth arctic expedition.

His target was to test the clothing, equipment and food under arctic winter conditions before beginning his expedition of 1894-97 to explore the north of Franz Joseph Land (80ºN), the expedition which would be called Jackson-Harmsworth arctic expedition.

|

| Frederick George Jackson |

The choose the Siberian Tundra because, as he himself says in the preface of the book:

"As most people are aware, the low Tundras of Arctic Russia and Siberia, although readily accessible and stretching on the east, west, and south to the confines of civilisation, possess a winter climate of a severity so great that it does not merely exceed the ri-gour of many regions lying farther north, and in the strict embrace of Oceanic ice, but actually reveals the lowest temperature yet recorded in the whole of the Arctic basin.

For it is on the frozen Tundras of Siberia that we find what has been called " THE POLE OF EXTREME COLD."

To me, personally speaking, Jackson is a character slightly unknown and it may be for many of you too. Almost all polar fans have always focused in those great explorers who, walking, sailing, by balloon or plane, either reached, or well just tried, theNorth Pole, the South Pole, the Northwest passage, etc. But we usually put aside those who made "detailed" explorations, to say something. Those expeditions focused only in a small part of the arctic geography, which had been previously discovered by others, and they carefully mapped them, measuring and recording all kind of scientific and meteorological data.In my case, I know Jackson above all becasue it was him who during that second expedition to Franz Joseph Land, stumbled by chance upon Nansen who was returning from his expedition towards the North Pole. Nansen story could have been different if that encounte hadn´t happened, that assertion still is matter of conjecture. It is possible that Jackson had saved Nansen´s life and it is also possible that if it weren´t for that encounter, Jackson would be one of those "secondary"explorers about who one hardly have heard a word.

|

| Jackson - Nansen encounter Junio 1896 |

With or without encounter, Jackson demonstrated to deserve the fame which now he partially has. He finished the survey of the archipielago discovered (at least first on claiming that) by the austrians Karl Weyprecht y Julius Von Payer en 1873. Cheated by the cursory precedent explorations, Jackson demonstrated that Franz Josef Land wasn´t a huge land extension which touched the North Pole, as it was the general believing, but an archipielago which its northern point was located not beyond 81ºN of latitude. Something similar happened to the danish expedition of Jorgen Bronlund, who, believing in the accuracy of Peary´s maps will end his days in the north of Greenland in 1908 together with other two colleagues.

Now than I am reading about Cook´s voyages, I realise how potentially hazardous was giving any credit to any existing map those days of exploration. No matter how reliable it could seem. Maps made after Tordesillas treaty move unscrupulously lands and islands to locate them in more convenient places, according to the need of every power. Fictional bays like that of Poctes (or Poetess) bay, in King WIlliam Land could have driven the Franklin expedition to a certain and slow death by starvation and scurvy in 1846, but the most astounding of all is that in relatively recent days in the twenty century, a wrong map could still kill well trained and equiped explorers as it happened in the case of the danish expedition. Me, thank goodness, never forget my GPS, and I wish it never abandoned me the day I really need it.

Now than I am reading about Cook´s voyages, I realise how potentially hazardous was giving any credit to any existing map those days of exploration. No matter how reliable it could seem. Maps made after Tordesillas treaty move unscrupulously lands and islands to locate them in more convenient places, according to the need of every power. Fictional bays like that of Poctes (or Poetess) bay, in King WIlliam Land could have driven the Franklin expedition to a certain and slow death by starvation and scurvy in 1846, but the most astounding of all is that in relatively recent days in the twenty century, a wrong map could still kill well trained and equiped explorers as it happened in the case of the danish expedition. Me, thank goodness, never forget my GPS, and I wish it never abandoned me the day I really need it.