The British Arctic Expedition led by George Nares during the years 1875-76 has perhaps always enjoyed an undeserved bad fame. It is commonly known as an expedition on which scurvy caused devastating effects in the health of the crews on board the ships Alert and Discovery, an expedition where four men died, three of them of scurvy.

The four men were:

Alert in Winter Quarters Floe Berg Beach

The expedition was also criticized for not having made any significant geographical discovery when they were intended to reach the North pole. Nares had apparently forgot the lessons which some other explorers, like Leopold McClintock, had learned about the use of dogs, snowshoes and the building of igloos from the Inuit during all the years that the Franklin search took place. Manhauling heavy loaded sledges was the prefered choice instead of the use of dogs which they have bought in Greenland and that likely was the decission which indirectly killed Porter, Hand and Paul.

Instead of serving as an example about "what not to do in a polar expedition", Nares´s expedition was the reference which Clements Markham (who accompanied the expedition till Disko Bay) decided to follow years after when he, as president of the Royal Geographical Society, planned Scott´s expedition to the South Pole, paving the path to the tragedy which would swallow Scott and his four companions in the Antarctic more than thirty years after.

George Henry Richards, Hydrographer of the Admiralty, shows his enthusiasm about the question of sledging and manhauling in the arctic regions in the Introduction of his Narrative when talking about the search of Erebus and Terror:

"Again, the search for the missing ships involved the minute examination of a vast extent of coast-line, which neither ship nor boat could approach, and this task could only be accomplished by the manual labour of dragging heavily laden sledges along the margin of the frozen sea for weeks or months together. The art of sledge-travelling in this manner was initiated, and perhaps brought to the highest state of perfection it is susceptible of, during the progress of this long search. As much as four hundred miles in a direct line on an outward journey had been accomplished by these means, each man dragging between two and three hundred pounds, including his provisions, clothing, and equipment, and being absent from the frozen-in ships frequently from ninety to a hundred days. It was manifest, then, that if such distances could be accomplished in search of men in distress, they could be equally well performed in the pursuit of geographical discovery".

But the Hydrographer was wrong, so was Nares who underlined Henry Richards views. McClintock had used 29 sledge dogs guided by a different Petersen during the Fox expedition of 1856-57. The use of dogs, the fastest and efforlessly way of travelling on ice and snow, was the proper way to perform any geographical discovery with surgery precission. McClintock and Hobson´s teams were so succesful precisely because they made an intensive use of dogs and built snow huts (igloos) to protect themshelves against the elements and the killing temperatures and lived off the land hunting and fishing when it was possible.

But not all of these critics are enterily justified. Actually, dogs were used in the expedition. Fifty five dogs were bought in Greenland (30 dogs were carried on Alert´s deck and 25 in the Discovery). Besides, some discoveries were made and some records beaten. They were the first on wintering at such high latitude (82º 17´), beat the previous record set by Hall´s expedition by a whole degree north reaching 83º 21' (that would last only six years before being beaten again by the Greely expedition for a magre new mark of two minute more) and there were also some heroic episodes worth of being rescued from the narratives of the expedition to be told here.

Albert Hastings Markham, second in command of Alert, cousin of the aforementioned Clemments, led the party aimed to reach the North Pole which abandoned the ship in april of 1876. Markham had some previous polar experience after having been second mate in the whaler Arctic a couple of years before sailing with Nares.

Markham later would write his own account of the voyage, from where we can surprisingly see his opinion about dog sledging:

"From six to ten or a dozen dogs form a team. They are capable of dragging as much as one hundred and fifty pounds per dog; but this is rather an excessive load and should not be exacted for any length of time. So strong and enduring are they that they will frequently perform a journey, over smooth ice, of twenty-five or thirty miles a day with this load; but with light loads and level ice they have been known to travel as much as seventy and even a hundred miles in one day."

But in spite of having them on such a high regard, Markham didn´t used the dogs. Nares and him considered them just an auxiliary mean of support and not the principal engine which could led the expedition to the glory. Scott himself would do the same thing years later. He didn´t built snow huts neither, disregarding McClintock´s succesful experiences. Tents can´t protect the explorers against strong gales, as Markham had learnt during the autumn explorations along the north shore of Ellesmere island. His analisys starts enumerating all the disadvantages involving the use of dogs:

"But when obstacles such as hummocks and deep snow-drifts have to be encountered, especially with a low temperature, the reverse is the case. Directly the sledge receives the slightest check from either of these causes, the dogs lie down, and look at you in the most provoking manner. It is no use having recourse to the whip, for not all the flogging in the world will make them advance until the obstacle has been removed, or the sledge carried over the difficulties that had retarded its progress"

And ends with a categorical judgement, perhaps sentencing those who accepted his advice to a sure failure in the subsequent expeditions:

"Another very annoying and distressing piece of work connected with dog sledging is clearing the lines, which in a short time become in a grievously entangled state from the constant dodging about of the dogs, and this it must be remembered has to be done with hands encased in thick woollen mitts, for to bare them would ensure serious frost-bites. In consequence of the amount of provisions that have of necessity to be carried for the use of the dogs, it is almost impossible to use them for long journeys. None were employed during the expedition by any of the extended sledge parties; but for short journeys, or when dispatch was required, they were invaluable."

The discussion about the use of dogs and other inuit techniques could fill a book, it is not my intention to start a debate here bout the question, but it is true that sometimes, we polar history enthusiasts have a trend to forget facts. Expeditions in the nineteenth century used dogs, though not always as the main mean of transport as they should have been used, but it is also true that more contemporary explorers, who we consider heroes like Shackleton, during his attempt to reach the south pole didn´t use them neither and are not blamed for it because they survived.

In september, once the Alert was anchored in his definite winter quarters, the exploration of the north coast of Ellesmere started. A party led by Aldrich ...:

"... was despatched with three men and two dog-sledges, provisioned for fourteen days, as a sort of pioneering expedition ; his orders being to proceed, if possible, as far as Cape Joseph Henry, there to erect a cairn and deposit a record with full information regarding the practicability of travelling, that would be of use to the main party which would follow him in a few days."

The main party formed by Markham, Parr and May departed three days after in three sledges, called Marco Polo, Victoria and Hercules respectively, dragged each by eight men carrying 90 kg each:

"Our provisions were all carefully weighed and packed ; the maximum weight dragged by each man on leaving the ship was 201 lbs., decreasing at the rate of 3 lbs. per diem due to the consumption of provisions. The slight experience that we obtained during the previous few days' sledging stood us now in good stead; the men who had recently been so employed being regarded as veterans in sledge work by those who were for the first time being initiated into its mysteries"

It is a pity that Markham doesn´t compared both experiences, one could think that the outcome was so different that he intentionally wanted to conceal any comparison:

"I make no apology for not entering more fully into the journeys performed by Aldrich and others, as the description of one sledging expedition suffices for all, and I am, of course, best able to describe those in which I was myself personally engaged."

That autumn exploration had to pay an expensive toll for just the 40 miles they covered in nineteen days. The toes of several members were amputated from their feet because of frostbitten once back to the ship. Among them the big toe of Lietuentant May.

In his narrative, Markham described the proceedings of the northern party without any self-critical thought. It was formed by 53 men and officers and seven sledges, some of which were intended to return before abandoning land. Two boats were carried on two of them. They departed the 3rd of april 1876, quite early in the season.

That wasn´t a regular sledge journey, but a constant battle against the ice since the very moment they put a foot on the frozen sea. In words of Markham:

" It seemed as if a terrible conflict had been fought between these ponderous masses of ice, which had so shattered and split them up as to suggest to us the idea that they resembled a tempestuous broken sea suddenly frozen."

Markham bore the hope that once they got far from the coast, the ice would become smoother and flat but that didn´t happen. They travelled during the night in order to avoid snow blindness making a snail-like progres, as Markham, called it. That would be the norm during the whole journey since they had to deal with pressure ridges fifteen meters high or more. Parry had had a similar experience fifty years before, he had been told that a cart could have been driven by a flat surface, dragged by reindeers, like in a highway, to the very north pole but there wasn´t any highway there. They had to cut their own way with their iceaxes exactly as Markham had to do. As he named it, they had to do the "Road-making".

Among the men who formed that party there was one who shone particularly among the others;

"Parr with pick- axe and shovel was a first-rate navvy," and worked like a horse."

"... large masses of ice thickly compacted together, squeezed up into every conceivable, but indescribable, shape and form to a height of about twenty-five feet; but these had to succumb to the strenuous exertions of Parr and his indefatigable road-makers"

But after two weeks of hard work, the scurvy showed up and got a deadly grip on almost the whole party. The terrain didn´t help neither so some of the men started to be unable to keep on dragging the sledges and had to be even carried on them.

By then, it was known that fresh meat and vegetables were effective against scurvy, but apparently the explorers weren´t able to secure it hunting to fight against the illess. Markham concludes that it was the absence of light, and the long confinement due to their wintering at higher latitudes than other expeditions, was the main cause.

It was the 20th of april and Markham, though complaining continuosly in his journal for the decreasing manpower and the extra weight the sick men meant, didn´t appear to think on returning to the Alert. It wasn't till 20 days after, the tenth of may, when he decided to turn around. In his narrative, Markham explains that he made up his mind because of the fact that: five men were completely useless, there were incresasing symptoms which the rest of the men were showing and besides, they only have provisions for 30 days for a retourning journey which was supposed to last 40.

"This 12th of May must always be regarded as an eventful day in the lives of our little party, for it was that on which we had the honour, and no small gratification, of planting the Union Jack on the most northern limit of the globe ever attained by civilized man, or, in fact, so far as our knowledge goes, by mortal man !"

|

| Captain Markham's most northerly encampment, by Admiral Richard Brydges Beechey |

Scurvy has the effect of decreasing the apetite of those who suffered it, in part, because of the pain which it produces in the sored gums, so the health of the men worsened exponentially. Fifteen days after, the party hadn´t reached land yet and desperate measures had to be taken:

"On the 27th the condition of the party was so critical that it became only too painfully evident that, to insure their reaching the land alive, the sledges must be considerably lightened in order to admit of a more rapid advance. The state of the party was on that day as follows: five men were in a very precarious condition, utterly unable to move, and consequently had to be carried on the sledges ; five others nearly as bad, but who nobly persisted in hobbling after the sledges, which they could just manage to accomplish, for, as the sledges had to be advanced one by one, it gave them plenty of time to perform the distance ; whilst three others exhibited all the premonitory scorbutic symptons. Thus only the two officers and two men could be considered as effective ! This was, it must be acknowledged, a very deplorable state of affairs"

This was the moment where lieutenant Alfred Arthur Chase Parr, came again into scene. The sledge was 30 miles far from the ship in the depot left the previous autumn on the way to Cape Joseph Henry. A message left in the cairn said that a dog sledge party has left the depot just two days ago, so they couldn´t expect another relief party coming soon. The situation was quite desperate and Parr was the stronger man, the only who still kept some strength and which could serve of some help. For the whole party it would have taken three weeks to reach the ship. The only way to avoid the explorers to end like the Franklin expedition retreating men, was to send the strongest man in search for help.

It was a bold chess move, the risks were too high. The history of Arctic exploration is full of examples of men who disappeared forever while traveling alone in the wilderness. A day after Parr left the party, the 7th of june, Porter died.

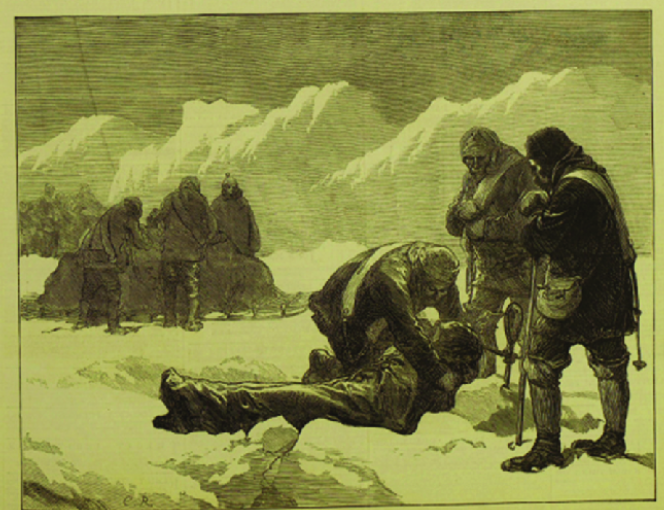

Not far from the depot left by the expedition the past autumn, what we supposed a swallow grave was dug:

"Sad and mournful, indeed, was the small procession that wended its way slowly to the new-made grave, dug out of a frozen soil, carrying the lifeless remains of their comrade, covered with the Union Jack, on the same sledge on which he had been dragged, whilst alive, for many weeks ; and there, with the tears trickling down their weather-beaten and smokebegrimed faces, with their hearts so full as to choke all utterance, they laid their late fellow- sufferer in his last resting-place.

A rude cross, improvised out of the rough materials that our own equipment supplied, with a brief inscription, marks the lone and dreary spot in that faroff icy desert where rests our comrade in his long sleep that knows no waking, and where probably human foot will never again tread."

" O World ! so few the years we live, Would that the life that thou dost give

Were life indeed ! Alas ! thy sorrows fall so fast, Our happiest hour is when at last

The soul is freed."

An sketch of Porter´s grave painted by the surgeon Edward Moss Lawton:

|

| THE MOST NORTHERN GRAVE A LITTLE mound of ice on the side of a floe-hill, and a rough cross made of a sledge batten and a paddle, mark our shipmate's grave — the most northern of any race or time. |

It was the 9th of june, a day after Porter had died and buried, when ironically, a dog sledge from the Alert shew up:

"...gradually emerging from the hummocks, a hearty cheer put an end to the suspense that wTas almost agonizing, as a dog-sledge with three men was seen to be approaching. A cheer in return was attempted, but so full wrere our hearts that it resembled more a wail than a cheer."

It took Parr a day to reach the ship and the rescue party another to come to rescue. More dog sledges came a day after and four days later, 14 of june, Parr's birthday, the whole party excepting for Porter, arrived to the ship.

Parr was a hero, however, Markham, again forgets to dedicate him a whole chapter, which is the lesser thing he deserved, in his book. He had saved the life of the remaining thirteen men from the northern party, including Markham´s one.

Nares, was more generous and recognized in his letters his bravery:

"Lieutenant Parr, with his usual brave determination, and knowing exactly his own powers, nobly volunteered to bring me the news, and so obtain relief for his companions.

Starting with only an Alpine stock, and a small allowance of provisions, he completed his long solitary walk, over a very rough icy road deeply covered with newly fallen snow, within twenty-four hours."

It is not mentioned in Nares notes that the forced march was performed by a dog sledge:

By making a forced march the two latter, with James Self, A.B., reached Commander Markham's camp within fifty hours of the departure of lieutenant Parr, although they were, T deeply regret to state, unfortunately too late to save the life of George Porter, Gunner, R.M.A., who only a few hours previously had expired and had been buried in the' floe"

Parr could have perfectly vanished and form part of the long list of polar casualties, securing a pin in my Arctic graveyard map but he survived and had still a long career after this adventure.

I was lucky enough to find a couple of good pictures of him. Parr died at the early age of 65 but left three daughters who had a long life. Robert Falcon Scott, during the Antarctic expedition of 1901-02 named a Cape after him. From the discovery of this cape, I have learnt that again, ironically, apparently, Parr was one of the Robert Falcon expedition advisors...

Shores of the polar sea : a narrative of the Arctic expedition of 1875-6

https://archive.org/details/b21356919/page/n3/mode/2up